Recently, I embarked on a weeklong journey along the Nile with my family and close friends, exploring Upper Egypt’s iconic sites—Luxor (ancient Thebes), Aswan (once Syene), and Abu Simbel—and immersing ourselves in its unique natural beauty. This trip marks the second of a series we plan to take as a family across the Nile Basin countries, following our first adventure in Tanzania.

During this journey, we spent much of our time in Aswan, the heart of modern Nubia, and one of the Nile’s most breathtaking regions. Unlike other parts of the river in Egypt, Aswan still retains pockets of protected wilderness, home to rich biodiversity, especially its abundant birdlife. Yet, like much of the Nile south of Egypt—shared by 11 countries—this delicate ecosystem faces increasing threats from human development.

The Nile, the world’s longest river, has long been the cradle of human civilization. For centuries, this majestic river has captivated explorers and travelers. It is believed that the first organized form of tourism emerged along the Nile during Egypt’s Roman era, while the 19th century saw the rise of modern chartered tours, with the first British Nile cruises setting sail.

This wasn’t my first visit to Upper Egypt. Growing up in Egypt, I had the chance to explore the region with my family as a child, which sparked my deep connection to it. Also, since founding my previous sustainable travel business in Canada in 2004, I’ve promoted ecotourism and organized many expeditions there.

In this article, I’ll share highlights from our recent trip—focusing on our birdwatching, sailing, and hiking experiences in Aswan—while shedding light on the growing threats to the river’s ecosystems throughout the Nile Basin. I’ll also explore promising initiatives aimed at restoring and protecting this magnificent river, ensuring its biodiversity and water resources endure for generations to come.

Our journey on the Nile in Upper Egypt

We began our journey in Luxor, often called the world’s greatest open-air museum. With about a third of the world’s ancient monuments, it was the perfect place to immerse my kids in Egypt’s rich history. We stayed on the West Bank of the Nile in a charming, family-run guesthouse nestled among lush green fields, just steps away from magnificent temples and monuments.

During our stay, we explored the Valley of the Kings, the Temple of Hatshepsut, the grand Karnak Temple, the newly restored Avenue of the Sphinxes and many other breathtaking sites.

One of our most memorable moments in Luxor was a donkey ride through the sugarcane fields of the West Bank. We were warmly greeted by locals, and the sight of birdlife, particularly the Cattle Egret, known locally as Abu Qerdan, was remarkable. Revered as the “farmer’s friend,” this graceful heron plays a crucial role in controlling pests by feeding on insects and worms in the fields. However, this scenic ride also brought to light a stark environmental issue: the irrigation canals feeding farmlands were clogged with illegally dumped waste—pollution that extends to the Nile itself, where motorboat traffic and waste disposal threaten the river’s fragile ecosystems.

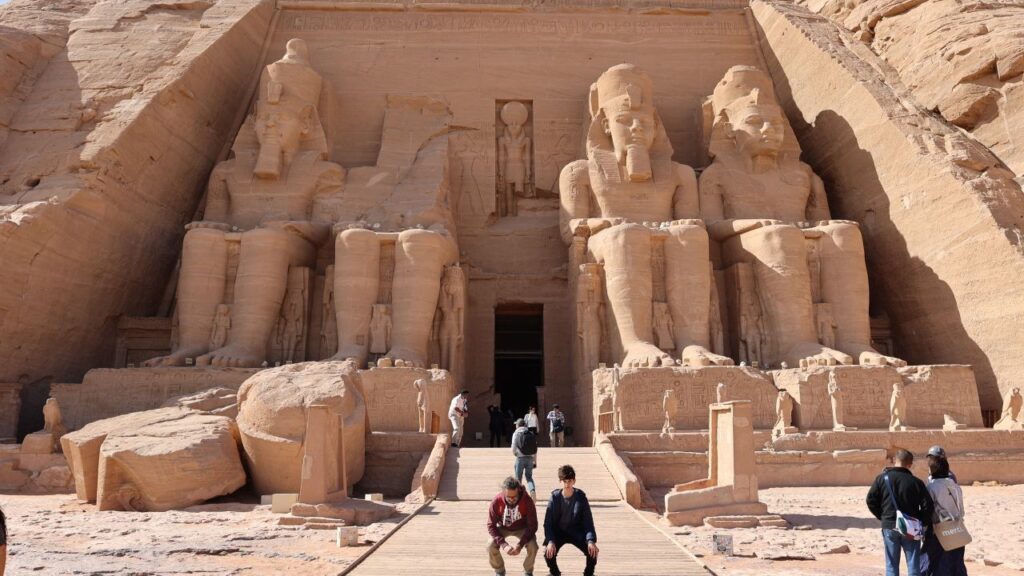

In Aswan, our focus shifted to outdoor and cultural activities, immersing ourselves in the region’s stunning landscapes, vibrant birdlife, and Nubian culture. We also visited historical gems like the Ptolemaic Temple of Isis on Philae Island and the grand temples of Abu Simbel on the banks of Lake Nasser. Instead of hiring a guide, I challenged my boys to take the lead and research the sites themselves. This approach allowed them to guide us enthusiastically, making the visits even more entertaining.

A highlight in Aswan was a day of birdwatching organized with Sobek Journeys, a local ecotourism expert. We spotted over 30 bird species, including the majestic Egyptian Goose, the Gray Heron, and the elusive Pharaoh Eagle-Owl. This birdwatching experience took place near Elephantine Island, where the Nile’s West Bank remains relatively unspoiled. Later, we sailed through the Saluga and Ghazal Protected Area, one of the last remaining pristine regions along the Nile in Egypt. The region faces immense pressure from population growth and tourism, underscoring the importance of strict protection to preserve its natural heritage.

We stayed on Heissa Island, a serene Nubian haven nestled between the Old Aswan Dam and the Aswan High Dam. Until just 15 years ago, the island remained largely untouched by tourism. Today, however, its unspoiled nature is transforming rapidly, as development encroaches at a swift pace. A memorable hike with Anouri, a warm-hearted Nubian guide, unveiled the island’s last remaining acacia and doum palm trees, along with its untouched southern and western shores, where natural lagoons provide refuge to diverse birdlife.

Aswan has become Egypt’s ecotourism frontier, with projects like Eco Nubia on Bigeh Island striving to embrace sustainability. However, many other initiatives fall prey to greenwashing, using cement and synthetic materials and leaving behind construction waste. Waste management remains a critical issue, and protecting the region’s natural heritage is key to ensuring that Aswan remains a cherished destination for years to come.

The cultural significance of the Nile

The Nile stretches over 6,600 kilometers (4,100 miles) and covers a drainage area of 3.2 million km², connecting eleven countries from Egypt to Burundi. It is fed by two main tributaries—the White Nile from Lake Victoria, and the Blue Nile from Lake Tana in Ethiopia. Although the White Nile is longer, the Blue Nile provides nearly 85% of the river’s water, especially during the monsoon season. This vast river system has been vital for civilizations for thousands of years, shaping the cultures, economies, and environments of the countries it flows through.

In Egypt, where rainfall is minimal, the Nile provides about 90% of the country’s freshwater. As Egypt’s population grows, concerns over water security have escalated, particularly with upstream projects like the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD).

Beyond its practical importance, the Nile was integral to ancient Egyptian culture and religion. The river’s annual inundation dictated the agricultural calendar, dividing the year into three seasons: Akhet (flooding), Peret (growing), and Shemu (harvest).

The Nile was sacred to the ancient Egyptians, represented by Hapi, the god of the river’s annual flood and fertility. Other deities linked to the river included Sobek, the crocodile god; Thoth, the ibis-headed god of wisdom; Khnum, the ram-headed god of the Nile’s source; and Heqet, the frog goddess of fertility. These gods symbolized both the nurturing and destructive aspects of the Nile’s floods.

Further south, the Nile was equally crucial to Nubian and Sudanese civilizations. The Kingdom of Kush, located in modern-day Sudan, rose as a powerful rival to Egypt, benefiting from the fertile lands around the river. The river’s cultural significance extends beyond Egypt and Sudan, reaching Ethiopia’s Lake Tana and Uganda’s Lake Victoria, where it remains central to heritage and livelihood.

The Nile’s rich ecosystems

The Nile’s ecosystems have been crucial to human evolution, from early Homo sapiens migrating along its fertile banks to the rise of Ancient Egypt. Today, despite threats from human activity and climate change, it remains one of the richest ecosystems on Earth, with diverse habitats including wetlands, floodplains, forests, and savannas.

The Nile Basin is home to 20 Ramsar sites, crucial wetlands that play a key role in water purification, flood control, and biodiversity conservation. Egypt hosts three of these sites, while Uganda has the most with twelve, along with additional sites in Sudan, South Sudan, and the DRC. These protected areas underscore the basin’s ecological significance and the vital services these wetlands provide.

In addition to the Ramsar sites, several UNESCO World Heritage sites are located within the Nile Basin. Among them are Uganda’s Rwenzori Mountains National Park, known for its glaciers, waterfalls, and endemic species, and Nyungwe National Park in Rwanda, one of Africa’s oldest rainforests. Also, two key Ramsar sites are on UNESCO’s tentative list: Lake Tana in Ethiopia and the Sudd wetland in South Sudan. The Sudd, the largest wetland in Africa, is home to the world’s largest land mammal migration, the Great Nile Migration, and remains one of the last intact ecosystems on Earth.

The Nile Basin is also linked to other significant ecosystems like the Simien National Park in Ethiopia, a key water source for Lake Tana and the Blue Nile, and the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania, widely regarded as the world’s most famous national park. During a family visit in December 2022, I was struck by the Serengeti’s lush, rain-fed landscapes and abundant wildlife—clear signs of the rainfall that drains into the Mara River and replenishes Lake Victoria, the main source of the White Nile. These connections underscore the vital role of distant ecosystems in sustaining the Nile’s flow.

Finally, the transboundary Virunga Mountain chain, shared by Rwanda, Uganda, and the DRC, is another crucial water source for the Nile. It is home to the world’s only remaining population of mountain gorillas, adding to its ecological and cultural significance.

The most threatened ecosystems on the planet

“Rivers are the lifeblood of our planet, yet human activity has poisoned, diverted, and dammed them with little regard for the consequences.” – David Attenborough

Over the past 50 years (1970–2020), freshwater wildlife populations have declined by 85%, according to the 2024 WWF Living Planet Report. In comparison, terrestrial populations have fallen by 69%, and marine populations by 56%. The main causes of biodiversity loss in river ecosystems are the construction of dams, irrigation canals, urbanization, tourism, industrial development, and pollution from agricultural runoff and industrial waste.

The Nile’s future is particularly at risk due to rapid population growth in its basin. Ethiopia, with around 135 million people, and Egypt, nearing 120 million, are among the largest contributors. Around 350 million people live within the Nile Basin, with 95% of Egypt’s population residing there. Africa’s fertility rate—approximately 4.5 children per woman—adds to the strain on the river, and while the rate is expected to decrease eventually, the coming decades will see continued pressure. Nile Basin nations, which represent about 50% of Africa’s population, will account for over 20% of the global population by 2100.

Biodiversity loss has already been significant in Egypt since the Aswan High Dam’s construction in 1970, as it blocks nutrient-rich sediments and disrupts fish migratory paths. Its impact, however, is not just ecological—the dam submerged a significant part of Nubia, displacing thousands and forcing UNESCO to relocate 22 major monuments, including Abu Simbel, to higher ground. Unfortunately, newly constructed dams continue to impact the river’s ecosystems with projects like the GERD in Ethiopia (2024), the Karuma Dam in Uganda (2023), and the Merowe Dam in Sudan (2009), led by China’s Sinohydro. In addition, large-scale irrigation schemes like those in Egypt and Sudan divert water, reducing river flow and impacting downstream ecosystems, especially those of the Nile Delta.

The demand for these infrastructure projects is further intensified by increasing agricultural investments from water-stressed Middle Eastern nations and China, facing mounting challenges in ensuring food security.

Alongside infrastructure projects, waste pollution is another growing threat. During our recent trip, we saw firsthand the severity of waste and plastic pollution, which spans the entire basin. Plastic waste not only harms the Nile’s freshwater ecosystems but also contributes to the Mediterranean’s worsening plastic crisis. The IUCN estimates that the Mediterranean contains 7% of global microplastics, despite representing only 1% of the world’s waters. In addition to plastics, heavy metals and chemicals from various sources are contaminating the river, further harming biodiversity and human health.

Promising conservation and restoration efforts

The Nile Basin’s ecosystems are at a critical crossroads. Rapid population growth, escalating agricultural demands, and large-scale infrastructure projects are placing immense pressure on the river, while pollution continues to escalate.

This critical situation is further compounded when vital aid programs, funded by development organizations, suddenly withdraw, as we are currently witnessing with USAID’s exit.

To safeguard the Nile, greater support from conservation bodies such as Ramsar, UNESCO, IUCN, and GEF, along with local and global NGOs like African Parks, is essential. Their efforts should focus on: (1) protecting highly threatened areas, such as those downstream in Egypt including Lake Burullus, Salouga and Ghazal in Aswan, and the Nile River Islands, and (2) establishing new protected areas while securing global recognition for biodiversity hotspots, such as the Sudd wetland in South Sudan and Lake Tana in Ethiopia.

Promising conservation initiatives are underway in the Sudd, led by African Parks, which manages Badingilo and Boma National Parks and aims to extend protection across the Boma-Badingilo-Jonglei Landscape (BBJL). However, these efforts face significant challenges, including a lack of local conservation skills and funding, as well as conflicts with local tribes who often distrust foreign interventions, rely on wildlife for food, and are thirsty for development.

Across the Nile Basin, conservation difficulties unfold in similar patterns. Governments face competing priorities, and the region is grappling with a shortage of skilled conservationists and rangers. Economic challenges and political instability have led to a significant exodus of professionals and skilled workers, with countries like Egypt losing conservation talent to Gulf nations, where investment in the sector is rising.

In light of these challenges, I recently had the opportunity to engage with leaders of several promising initiatives focused on preserving and restoring the Nile. These discussions revealed innovative solutions that could play a crucial role in safeguarding the basin’s future.

A key effort is the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI), established in 1999 to promote sustainable water management. Germany has been a major supporter, funding projects like the ongoing GIZ initiative to reduce Nile plastic pollution. Another promising initiative is Clean Rivers, a UAE-based NGO focused on tackling plastic pollution in river systems.

Grassroots efforts are also gaining momentum. During my visit to Aswan, I met Mongy, founder of Nile Journeys, a community-driven initiative working to regenerate the river and to solve the waste problems. Further north in Cairo, VeryNile has mobilized thousands of volunteers and partnered with 180 fishermen to remove nearly 500 tons of waste from the river.

In tourism, ecolodges like Eco Nubia promote the use of local materials and waste reduction, while bird conservation programs—such as the one initiated by Heissa Camp’s founder, Hashim Morsy—highlight the region’s rich biodiversity and the need to protect it.

Moreover, some Nile Basin countries like Rwanda, Kenya, and Uganda have made significant progress with plastic waste bans—steps Egypt should follow.

Beyond conservation and waste management, we must go further—assessing the full environmental costs of hydropower and exploring alternatives, especially solar. Egypt has taken the lead with the Benban Solar Park near Aswan, a 1.65 GW powerhouse rivaling the capacity of the Aswan High Dam. Meanwhile, distributed solar companies like Ignite Power are rapidly expanding, bringing clean energy closer to communities across the region.

As Herodotus, the ancient Greek historian known as the “Father of History,” famously said, “Egypt is the gift of the Nile.” For millennia, the river has been Egypt’s lifeblood. But preserving the Nile requires a fundamental shift in perspective. We must view it not only as a water source for human consumption but as a living organism, supporting interconnected ecosystems that provide essential services to humankind.

The upcoming IUCN World Conservation Congress in Abu Dhabi and the Cairo Water Week in October will provide ideal platforms for fostering dialogue among Nile stakeholders. The future of the Nile depends on continued collaboration among conservation organizations, governments, and communities to protect and restore its vital ecosystems.

Reflecting on my journey, I look forward to exploring more of the Nile Basin with my boys. I also hope that one day, they will return to Aswan with their own children, discovering an even richer biodiversity and a more pristine nature than we were fortunate enough to witness.

Leave a Reply