Our family adventure in Bhutan — or Drukyul, the Land of the Thunder Dragon — was one of the most memorable trips of our lives. Over two weeks, we felt as though we had traveled back in time to an era when humanity was still deeply rooted in the natural world.

The journey unfolded in two parts. The first week took us deep into the inner Himalayas of Central Bhutan on a challenging camping and hiking expedition. The second offered a gentler immersion into Bhutan’s rich cultural traditions — from sacred Buddhist art and music to crafts and, most delightfully, its culinary heritage.

I was incredibly proud of my two boys, then 13 and 10, who completed a demanding four-day hike through forests and hills, covering over 40 kilometers. Along the way, we met the Monpas – Bhutan’s Indigenous people and earliest known inhabitants — and witnessed the extraordinary biodiversity of the pristine Himalayan forests, particularly within Jigme Singye Wangchuck National Park.

My wife, choosing wisely, joined us for the second part of the journey.

Bhutan is a truly rare destination – not only for the warmth of its people, its striking Buddhist culture, and dramatic landscapes, but for the deep ecological consciousness woven into its national identity. It is the world’s first carbon-negative country, absorbing more carbon than it emits, and the only nation to measure progress through the Gross National Happiness Index (GNHI) – a holistic alternative to GDP that places nature conservation among its four core pillars.

Protected by its mountainous terrain and relative geographic isolation, Bhutan remained largely untouched by colonization. It was unified only in the 17th century and became a modern kingdom in the early 20th century under the Wangchuck dynasty, which still reigns today.

This essay begins with a journey through our two weeks in Bhutan, before delving into the country’s life philosophy and its pioneering approach to conservation and sustainable tourism. I then reflect on the spiritual foundations of Bhutan’s environmental ethic, concluding with lessons that may inspire other nations – large and small – in their own search for harmony between nature, culture, and development.

Part 1 of the journey: Into the wilds of Central Bhutan

I arrived in Bhutan with my two boys on a sunny April day, just as the rhododendrons began to bloom. The plan was to spend the first half of our trip together, just the three of us, taking on a more physically demanding adventure through the wild heart of Central Bhutan. My wife would join us later for a gentler itinerary focused on culture, spirituality, and the arts.

The highlight of that first week was a 40-kilometer, four-day trek through the inner Himalayas, linking the Indigenous Monpa communities of Jangbi, Kudra, Nabji, and Korphu within Jigme Singye Wangchuck National Park.

On the way to the trailhead, we visited sacred landmarks: the 108 chortens at Dochula Pass, Wangdue Dzong, Chimi Lhakhang, and the towering Chendebji Chorten.

For four days, we were the only foreigners in the entire area. Our guide, Rinzin, was exceptional – a passionate ornithologist and walking encyclopedia of Bhutanese flora, fauna, and Buddhist tradition.

The forest came alive around us. Curious golden langurs and rhesus macaques peeked out from the trees. The air rang with birdsong – we spotted over 50 species, from great hornbills and thrushes to pheasants, falcons, barbets, cuckoos, and bulbuls. Many more called to us from the dense canopy, heard but unseen.

The plant life was equally enchanting. In this subtropical zone, the trails were lined with chestnuts, oaks, pines, needlewoods, and even wild cinnamon trees. We walked under crimson rhododendrons, purple jacarandas, and delicate white angel trumpet trees. Ferns and stinging nettles brushed our legs as we hiked.

Our path followed an ancient pilgrimage route linked to Guru Rinpoche (Padmasambhava), the 8th-century mystic who introduced Buddhism to Bhutan. Many sacred sites along the way are said to be home to spirits – both benevolent and mischievous – that still dwell in the forest.

One of the most mystical moments came when we camped near Kudra village, beside its old Buddhist temple. Once home to a small community, Kudra is now a ghost village. That night, under a star-filled sky and completely alone in the valley, we felt the weight of time, silence, and presence — a rare kind of stillness.

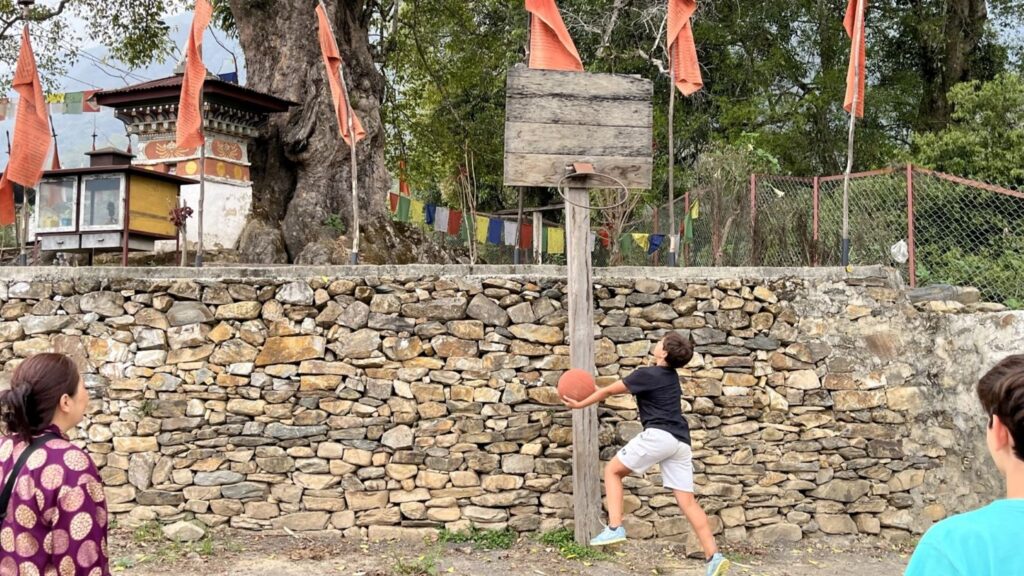

In Nabji, we were welcomed with a traditional dance performed by village women. Later, we played basketball under the watchful gaze of an ancient sacred Bon tree and shrine. That afternoon, we joined a cooking workshop in a traditional home, using a 600-year-old iron pan, and visited a hardwood-and-stone house under construction – a beautiful fusion of practicality and timeless craft.

Part 2: A spiritual and cultural immersion

On the sixth day, my wife joined us in the serene Phobjikha Valley, where we reunited at a traditional farmhouse homestay surrounded by green pastures and sweeping views. Our hosts, Tshering and his wife, welcomed us with warmth and introduced us to the lady who owns the home — a descendant of a former Je Khenpo, Bhutan’s chief spiritual leader. We sipped rich butter tea and milk tea by the wood stove as the mountain winds whispered outside.

The landscape was breathtaking — soft rolling hills, grazing yaks, and endless skies. Over two days, we hiked within the RSPN-protected area (Royal Society for Protection of Nature), walked the Gangtey Nature Trail, and visited the Gangteng Monastery — a 17th-century Nyingma center where black-necked cranes famously circle above upon arrival — and the Kunzang Choling Shedra, a Buddhist school home to 300 young monks.

At the Black-necked Crane Education Centre, we learned about these remarkable birds’ 1,000-kilometre migration from the Tibetan Plateau each winter, their dependence on the valley’s marshy wetlands, and the community-led monitoring program that tracks each bird’s arrival and departure to help ensure their continued survival.

We then made our way to the Sangchen Dorji Lhendrup Nunnery, perched high atop a forested mountain. We spent the night there, joining the nuns for their evening prayers and chants – a quiet, deeply moving experience.

The next day, we explored Punakha Dzong – our favorite of the dzongs – rising at the confluence of two rivers. We then visited the Buddha Dordenma, a gilded 51.5-meter bronze statue overlooking Thimphu valley. Later that day, we caught a glimpse of Bhutan’s elusive national animal, the takin – a large, shaggy herbivorous mammal that looks like a cross between a goat and an antelope – at the Motithang Takin Preserve.

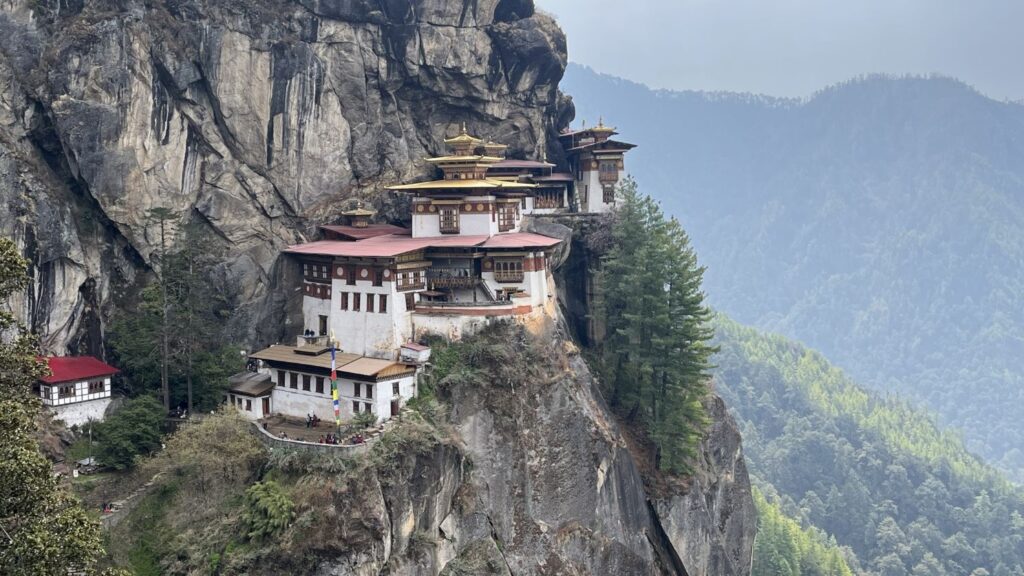

Our pilgrimage culminated in a demanding three-hour climb to the Tiger’s Nest monastery, scaling 700 steps carved into the cliffside. Reaching the monastery – seemingly suspended in air – felt like touching the sky. That evening, we soaked in a traditional hot stone bath while watching the sunset over Paro valley.

On our final day, we joined the Rhododendron Festival at the Royal Botanical Park, where families celebrated the arrival of spring among the blooming flowers.

I also had the opportunity to meet Dr. Karma Dorji and her team at Bhutan’s National Biodiversity Center to learn more about their biodiversity strategy and plans ahead of COP16 – the Biodiversity COP in Cali, Colombia, where I had the pleasure of reconnecting with her a few months later.

A culinary adventure

Bhutanese cuisine was easily among the spiciest we’ve ever encountered. We became connoisseurs of ema datshi – the beloved chili-cheese national dish – and discovered delicious Bhutanese dishes like fiddlehead ferns, puta buckwheat noodles, and snow trout. Even breakfast was a surprise – often featuring spicy fried rice paired with fiery ezay chili paste.

On two unforgettable occasions, we bought yak cheese directly from high-mountain herders. This cheese was so dense and aged it was nearly tooth-breaking — a small price to pay for tasting a true highland delicacy at its source.

But perhaps the most memorable meal was at the home of Dema — Tshering’s sister and part of the same family-run travel business. Her warm hospitality and homemade dishes came together in one of the best meals we’ve had anywhere, ever.

Bhutan’s philosophy of life and nature conservation

Bhutan is one of the most conservation-committed countries in the world. Its constitution mandates that at least 60% of its land remain under forest cover – a target it has exceeded, with around 70% still forested today. Over 50% of the country is officially protected, giving Bhutan the highest conservation coverage in Asia, and one of the highest globally.

Among Bhutan’s most remarkable features is its nationwide network of biological corridors, which legally connect all protected areas into a single contiguous landscape. This system allows for uninterrupted wildlife movement – vital for species like the Bengal tiger, snow leopard, and Asian elephant.

Throughout our journey, we were consistently struck by the pride that Bhutanese people express in their country’s development philosophy, which is rooted in preserving both natural and cultural heritage. This philosophy is embodied in the Gross National Happiness Index (GNHI) — Bhutan’s groundbreaking alternative to GDP — which measures national progress through holistic well-being, including environmental conservation, cultural resilience, and good governance.

Despite its small size and mountainous geography, Bhutan has emerged as a global leader in ecotourism. Its “high-value, low-volume” model limits mass tourism in favor of long-term sustainability. In 2023, Bhutan ranked 6th in Forbes’ Global Ecotourism Index. While the $100 daily sustainability fee per traveler may deter some visitors, it helps fund conservation and social programs while preserving the country’s fragile ecosystems.

This conservation ethic is visible not only in policies and planning but also in lived traditions. During our visit to Phobjikha Valley, we witnessed a striking example: the entire valley is protected to support the winter migration of the black-necked crane – a community-led initiative that blends biodiversity stewardship with local pride and celebration. Similarly, just outside Thimphu, the Takin Preserve reflects national commitment to biodiversity — not only as an ecological resource, but as part of the country’s cultural identity.

What struck us most – beyond Bhutan’s natural beauty and dramatic landscapes – was the kindness, humility, and grace of its people. These values were felt in every encounter. At the Rhododendron Festival in Lamperi, for example, we sat beside local families – and beside Bhutan’s Minister of Energy and Natural Resources, Lyonpo Gem Tshering. With no special fanfare or VIP separation, the Minister quietly thanked guests as he made his way out, shaking hands and showing sincere appreciation.

It was in that moment – and many others – that we began to understand how this humility and care for others extends to the way Bhutanese people treat the land, rivers, forests, and the living world around them.

This deep ecological consciousness is not only a matter of policy or planning – it is woven into Bhutan’s spiritual worldview, where nature is not separate from human life, but sacred and alive.

Bhutan’s spiritual connection to nature

This journey constantly reminded us of our interconnectedness with the natural world – not only through Bhutan’s breathtaking valleys and forests, but through its ancient stories, Buddhist traditions, and sacred shrines and groves.

The most profound of these stories were those we encountered during our four-day trek in the footsteps of Guru Rinpoche. Our guide, Rizin, shared his deep knowledge and passion for Bhutanese Buddhism, especially the teachings that shape the relationship between humans, nature, and the spirits of the forest.

While parts of modern Bhutanese society are changing – especially in urban centers increasingly exposed to global consumer culture – many Bhutanese continue to integrate core Buddhist values into daily life, with a strong reverence for all living beings.

This compassion is deeply rooted in spiritual teachings and myths found in temples, sacred groves and home altars alike. One of the most important deities is Chenrezig, the Bodhisattva of Compassion, who vowed to remain in the cycle of existence until all beings are freed from suffering. His image, often depicted with four arms, stands alongside those of Shakyamuni Buddha and Guru Rinpoche. His mantra – Om Mani Padme Hum – is etched into prayer wheels, carved into stones, and chanted across the country.

This nature-based spirituality is visible not only in grand monasteries, but in small stupas and roadside shrines, and even in quiet corners of family homes. At our homestay in the Phobjikha Valley, we discovered a shrine room tucked just beside our bedroom – a space of daily devotion that brought the sacred into the domestic.

In Bhutan, biodiversity is not just a backdrop to spiritual life – it is a living expression of it. Many species are revered not only for their ecological importance, but for their spiritual meaning. The takin, for example, is not merely Bhutan’s national animal; it is also a creature of legend, said to have been created by the 15th-century yogi Drukpa Kunley from the bones of a cow and a goat. When we visited the Takin Preserve in Thimphu, these strange, majestic animals felt like a bridge between the mythical and the real.

Likewise, the black-necked crane holds a special place in Bhutanese Buddhist belief. These graceful migratory birds are considered heavenly messengers. When they arrive in the Phobjikha Valley each winter, communities celebrate with festivals and rituals. During our visit, we walked the prayer-flag-lined trails near the observation center, surrounded by wetlands and mountain silence. Locals told us how the cranes circle Gangteng Monastery upon arrival — a gesture seen as an act of devotion. That story stayed with me not only as a beautiful legend, but as a powerful example of how reverence becomes conservation.

This spiritual ethos also protects landscapes. In Bhutan, many mountain peaks and forested valleys are considered abodes of deities and spirits. These beliefs serve as cultural boundaries: sacred landscapes are left untouched. For example, Mount Jomolhari is believed to be the home of a goddess, and traditional norms forbid climbing it – a conservation measure rooted in faith rather than regulation. In this way, Bhutanese Buddhism transforms biodiversity into a sacred inheritance. To protect the natural world is not just an ecological duty – it is an act of devotion.

Bhutan’s spiritual connection to nature also extends beyond Buddhism. In the village of Nabji, we witnessed the enduring animist traditions of the Monpa people. At a sacred cypress tree altar, locals lit butter lamps and offered prayers – practices rooted in Bön, the ancient pre-Buddhist tradition of the Himalayas. These beliefs continue to coexist with Mahayana Buddhism, particularly in remote regions, reflecting a rich, layered spirituality grounded in place.

Importantly, this reverence is not confined to the spiritual realm. Bhutan’s public institutions reflect the same ethos of respect and balance. Nowhere is this more visible than in the Dzongs – majestic fortresses that serve as both monastic centers and administrative capitals.

Each Dzong houses the office of the regional governor (Dzongdag) alongside a resident monastic body. The Dzongs we visited – Punakha, Wangdue, and Tashichho – were built in the 17th century and beyond. Often perched above river confluences or nestled into mountain folds, they are perfectly placed to align with both spiritual and natural forces. With their seamless integration into the landscape, the Dzongs embody a worldview in which governance, spirituality, and nature are not separate domains, but parts of a single, harmonious whole.

Takeaways for other nations

Bhutan is a leading nation and champion of nature conservation, one that has succeeded in integrating the core values of nature stewardship into the fabric of its society – through its political system and regulations, spiritual traditions, and cultural norms. It is the first carbon-negative country and the only country in the world to have legally connected all of its protected areas through ecological corridors.

Here are key takeaways and lessons learned for other nations that I look forward to discussing at the upcoming IUCN World Conservation Congress in Abu Dhabi in October 2025.

- Conservation and nature connectivity. Bhutan is a trailblazer when it comes to nature connectivity. It is the only country in the world where the entire protected area system is legally connected by a nationwide corridor network, forming a single contiguous conservation landscape. As nations integrate the UN CBD and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KMGBF) alongside the 30×30 initiative to protect 30% of land and sea by 2030, connectivity must become a core conservation principle – ensuring species can move freely across landscapes and mitigating the impacts of habitat fragmentation.

- Takeaway: Without connected landscapes, protected areas risk isolation and degradation – connectivity is essential for resilient ecosystems and biodiversity survival.

- There is no progress without nature. Bhutan was among the first to adopt an alternative to GDP, the Gross National Happiness Index (GNHI), which measures progress holistically, integrating nature conservation, cultural preservation, and good governance alongside sustainable development. Following Bhutan’s lead, countries like the UK and Canada now incorporate nature and wellbeing into their national metrics. China has introduced the Gross Ecosystem Product (GEP) to account for natural capital and incentivize conservation and restoration.

- Takeaway: Redefining progress to include nature’s value is critical for sustainable futures – economic growth must be balanced with ecological health.

- Tourism can support conservation. Mass tourism and overtourism can devastate natural environments and local communities. Bhutan understands these risks and has successfully positioned itself as a world-class, high-end sustainable tourism destination. Its low-volume, high-value tourism model channels revenues into conservation through sustainability fees and park entry charges, attracts responsible travelers who respect nature, and nurtures a local ecotourism industry.

- Takeaway: Thoughtful tourism policies can turn visitors into stewards and funding sources for conservation – quality over quantity matters.

- Appreciating nature starts with compassion. One of the most striking traits of Bhutanese people is their humility and kindness toward others and all living beings. This compassion is a core Buddhist teaching and echoes older nature-based spiritual traditions in Bhutan, fostering a unique respect and appreciation for biodiversity.

- Takeaway: Cultivating compassion for nature at the societal level is foundational – all nations can benefit from nurturing empathy toward the living world.

- Nature is an integral part of culture. Nature appreciation and compassion permeate Bhutanese society across social classes, creating a culture that prioritizes nature and tradition over consumption and exploitation. Rooted in Buddhism, this cultural identity fosters a deep sense of belonging to the Himalayas and the broader natural world. Both Bhutanese and visitors benefit from the cultural ecosystem services provided by pristine nature. While most cultures value nature to some extent, many societies still have work to do in embedding these values throughout their communities.

- Takeaway: True conservation requires culture-wide integration of nature-based values – building societies that cherish nature as part of their identity is essential for long-term stewardship.

Bhutan’s broader ethos – valuing biodiversity, tradition, and coexistence between humans and wildlife – has made it a global model of proactive environmental stewardship. The country has achieved a rare balance between development and preservation that many nations strive for but few attain.

Yet as many young Bhutanese leave the country in search of greater economic opportunities abroad, the future raises important questions: Can Bhutan continue to thrive while safeguarding its natural environment for generations to come? How can it create meaningful livelihoods at home without compromising its forests and wilderness? And will ambitious projects like the Gelephu Mindfulness City succeed in rebalancing tradition and conservation with the pressures of modern development? These are questions for Bhutan’s people to decide, but I remain confident this remarkable nation will continue to serve as a global example in environmental stewardship.

My trip taught me that effective conservation relies on more than laws and policies – it depends on deeply rooted cultural and spiritual values that connect people to the natural world. Bhutan shows how governance, tradition, and community respect can work together to protect the environment while fostering sustainable development. As environmental challenges intensify worldwide, Bhutan offers a practical model for balancing progress with conservation. I hope its example inspires other nations to deepen their own commitments to nature in meaningful ways.

Leave a Reply